What the Brain’s Function Tells Us About Artificial Intelligence (Putnam Series, Pt. 3)

Consciousness, intelligence, and the paradox of prediction.

As I shared in my last post, the key motivation for Peter Putnam to develop his functional model of the brain is to explain the observer effect in modern physics. He warned that physics would get to a dead end if we don’t consider mind and matter as a whole system. I think his warnings apply to today’s AI development as well, so today, I ‘d like to share a few insights that I draw from his work with you.

Consciousness Is the Engine of Intelligence

The relationship between consciousness and intelligence is a hotly debated topic. There is a popular perspective in the circle of artificial intelligence that trivializes consciousness. Consciousness is either considered separate from intelligence (LLM is so smart without consciousness), or a byproduct of intelligence (LLM is so smart now such that it has become conscious).

I have long doubted such a stance and Peter Putnam’s framework gives me a solid ground to reason about their relationship.

In Putnam’s framework, the human brain is viewed as a parallel digital information processing system, which, through evolution and contradiction resolution, creates our abstract “words” and heuristics. Those words define our perceived reality, and those heuristics dictate how we behave.

Our consciousness (subjective feelings) connects us to the “matter”, and it is the engine that shapes our words and heuristics. Most importantly, the feeling of contradiction (surprised, nervous, hesitant, embarrassed, etc) rises when several heuristics get triggered while pointing to different next words. The resolution of contradictions leads to the formation of new words and refinement of heuristics.

We can infer the existence of matter (the objective truth) because we see there are “person independent components” in different people’s heuristics. However, matter couldn’t be fully known, because our consciousness is contradiction focused. When old contradictions are solved, we discover new contradictions and that in turn reshapes our reality.

As one can see, what we define as intelligence in Putnam’s model is the ability to resolve contradictions; however, it is our consciousness that discovers contradictions to resolve. Because our consciousness connects to the matter, it provides the ground truth that is not in our existing words and heuristics, which is the source of innovation.

Intelligence Is about Contradiction Reconciliation

That intelligence is about reconciliation of contradicting heuristics is such a profound insight.

In my 2024 post Learning: Fast & Slow, I conjectured that the biggest difference between LLM and the human brain is the “slowness” we learn. At school, when facing a brand new concept, I tended to learn very slowly at the beginning, but after I got past that phase, I learned much faster and remembered them for a long time. To interpret this phenomenon in Putnam’s model, I learned very slowly because I saw a lot of contradictions with my existing heuristics at the beginning, so I had to spend lots of energy reconciling with my existing knowledge. But once that hardest reconciliation was done, learning the derived concepts becomes simple inference.

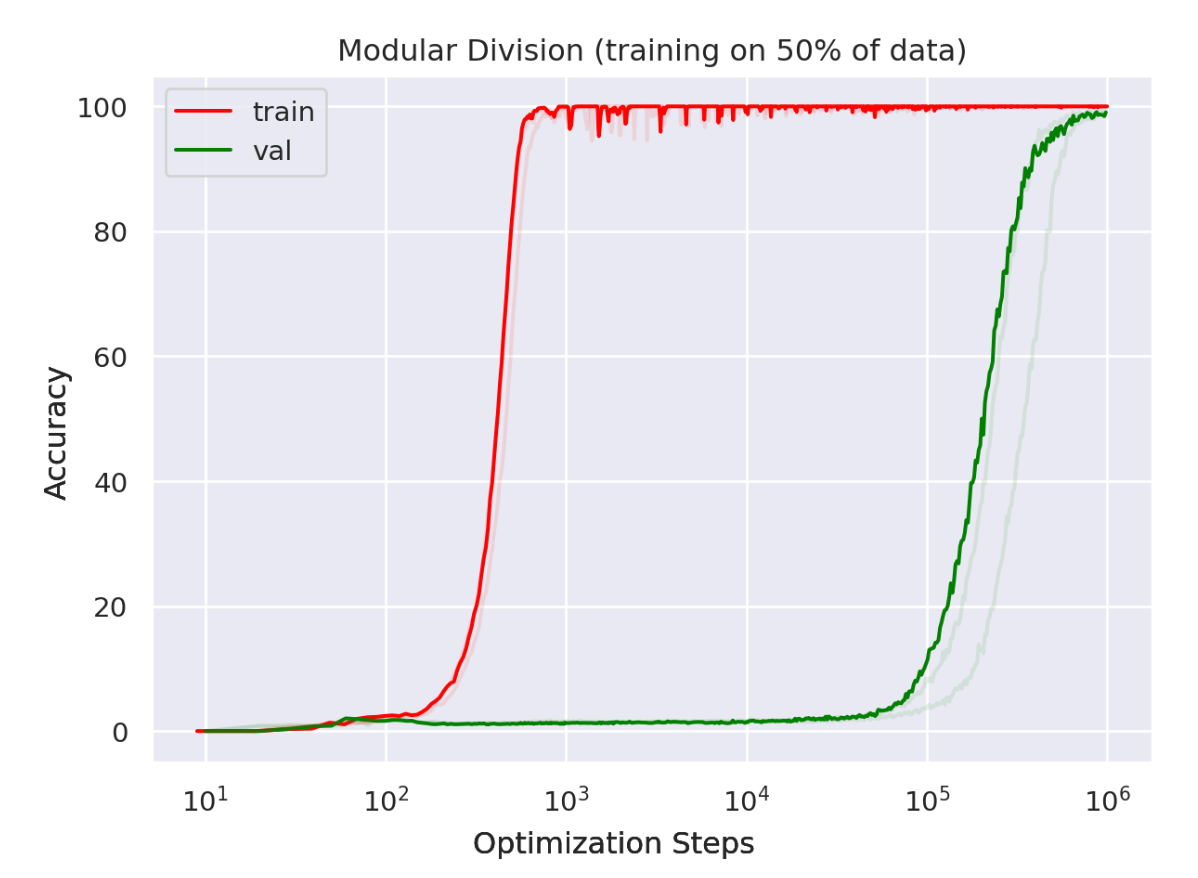

We see a rudimentary version of reconciliation in the “grokking” phenomenon during deep neural network training. When a large (over-parameterized) neural network is trained with an insufficient amount of data, the training accuracy quickly reaches perfect level, while validation accuracy stays at random guess level, showing severe over-fitting. The generalization happens after training the model for much much longer. If you only look at the training error, it seems little is happening after reaching perfect accuracy. Underneath however, the neural network is restructuring, cleaning, transitioning from memorization to learning the underlying mechanics.

But the grokking phenomenon seems to take an opposite route compared to how humans learn. It starts from over specific heuristics (memorization) to achieve generalization, while humans, according to Putnam, start from overgeneralized heuristics. Grokking doesn’t achieve the type of generalization humans have, and it requires a lot more examples than humans do to generalize.

Human-type reconciliation doesn’t happen in today’s LLM training. Because of that, during inference time, millions of possible actions get triggered at the same time, when they compete for emission through the final “softmax” layer. Without reconciliation, deep neural networks remain highly energy inefficient, and they won’t have a true understanding of the mechanics behind the training data.

Better Predictions Won’t Take Away Our Decision Making

One of the questions that Putnam tried to answer with his model of the brain is a classical paradox in physics - if nature is deterministic as physics indicates, where does our sense of free will come from? If one’s behavior can be perfectly predicted, wouldn’t the prediction itself change our behavior, rendering the prediction wrong? His answer to that question should help clarify some concerns about AI and technology as well.

Of all the concerns about AI, the least to worry about is that AI may get much better at predicting the outcome than ourselves, such that we outsource all our decision making. Why is that? Because that’s not how our brain works.

When we carry out our life tasks, our heuristic gets triggered to predict the next word. If there is no contradicting heuristics triggered at the same time, we just go emit the action, almost subconsciously. Otherwise, if there is a contradiction, our attention is raised to resolve it. More compute resources are accrued for two sets of neurons to fight for a winner. Sometimes, that resolves the contradiction, but other times, the resolution becomes a new task, which triggers other heuristics.

AI, trained on our perceived reality, is becoming part of our heuristics just like physics. However, since we own our consciousness, we will always be the one that feels the contradictions and seeks the resolution. We are always the decision maker; better heuristics just help us make better decisions.

In fact, if AI truly becomes a reliable and better predictor for our long term benefit than ourselves, it would be the best growth coach that everybody wants to have. And such a coach would sometimes advise us to make our own decisions without giving their advice, because exploring and learning is where we get our deepest sense of fulfillment.

The thing people are actually worried about AI is not that they make better prediction than us, but that they are not better than us - unreliable, optimized for the system instead of us, or, optimized for short term instead of long term, etc - and yet, they trick us into believing so, or, they are forced upon us by the system such that it limits our option space.

What’s Next?

After this post, I am going to pause my Putnam series for now. Putnam’s unpublished work online covers lots of other topics, including his philosophy of living a modern life, his perspective of the great men phenomenon, etc., which are equally thought provoking, and to some extent, explain why he chose an unusual life trajectory. If you found those topics interesting, or if you would like me to elaborate on topics covered in the series of posts, feel free to leave a comment!