Long Live Engineering

The engineering mindset - the relentless pursuit of building useful layers, and the courage and the ability of peering through the complexity of underlying layers, will thrive forever.

Over the years, I had lots of career growth conversations with other engineers. In the last two years, added to those conversations are questions on whether software engineering, or engineering in general, will still be relevant in the near future. As a parent, I have been told that knowing “how to do” will no longer be needed, and parents should just let kids play and entertain, because that’s how they learn “what to do”. Such advice has a caveat - some kids are genetically drawn more to the how rather than the what. Can these kids still have a fulfilling career in the future?

In this post, I will share my perspective on these questions - from engineer growth to the relevance of engineering in the future world. But we have to start by answering a fundamental question - what is engineering?

A vast majority of us live in a modern life where the environment is wrapped by safe, convenient and pleasant interfaces. Roads are paved, separated into lanes by clearly marked lines. Pressing a button turns nights into day time and summers into spring. The most magical interface is of course the digital screen - a physics-defying interface where the only constraint appears to be your imagination.

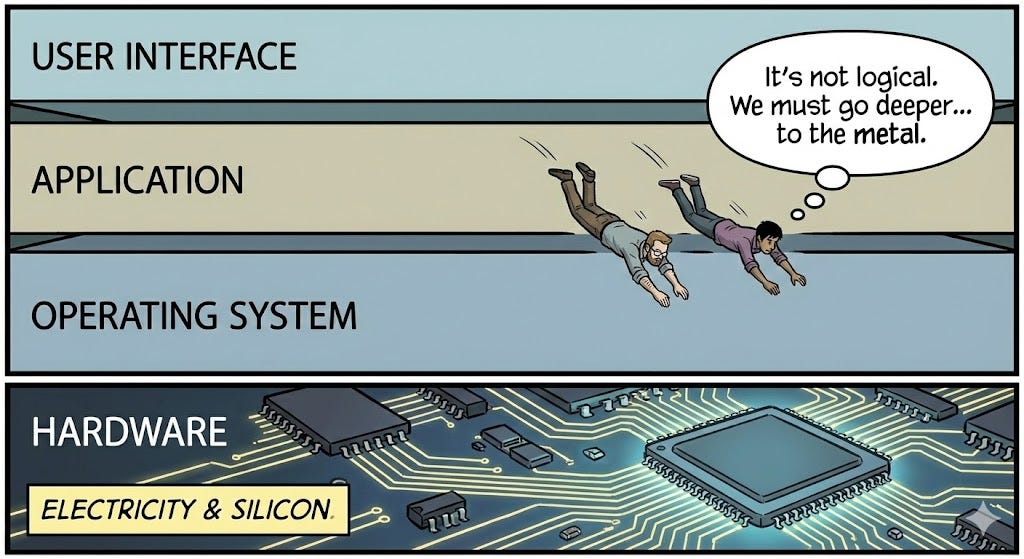

These end user facing interfaces are built on top of layers and layers of abstractions. Each layer does a lossy compression of information from the previous layer. It hides the previous layer’s complexity, providing a more convenient interface for the next layer.

Integrated circuits, Turing machines and software APIs are powerful abstractions that enable the magic of the digital screen. But if you go one layer down, these abstractions disappear. You don’t see Turing machines from the circuits layer; you see limited memory and faulty hardware. You don’t see boolean circuits if you go down to physics; what you see is space-time constraints and quantum effects. Unwrapping the implementation of an API, you see nuances, tradeoffs and likely bugs as well.

When the interfaces are working as intended, life is very simple. You don’t need to understand the previous layer’s mechanism. You just follow the simple logic provided by the interface and you get what you want. However, because of the layers of lossy abstractions, the interfaces are doomed to break down or underperform in certain occasions.

An engineer’s job is not to build what they are asked to, assuming the existing interfaces work. Engineering is about designing, building, maintaining and improving interfaces for the next layer in spite of the complexity of the previous layers. To build and maintain the interfaces, it requires peering through layers and layers of abstraction to root cause problems and bottlenecks and figure out the right solution.

There are lots of fascinating engineering stories where you need to consider the full stack to investigate and come up with a solution. The story of Jeff Dean and Sanjay Ghemawat is a well-known one, where they pinpointed and overcame the hardware error that caused Google’s search index to become months stale. But my favorite software engineering story isn’t about saving a search index; it is about a rescue mission 15 billion miles away: the 2024 Voyager 1 memory hack.

Here is a summary of the story written by Gemini:

In late 2023, Voyager 1, humanity’s most distant spacecraft, suddenly began sending back repeating gibberish instead of readable science data. Engineers at NASA had to peer through the layers of telemetry to diagnose a physical hardware failure: a single chip within the Flight Data Subsystem - a computer designed in the 1970s with incredibly limited memory - had died. This specific piece of faulty silicon held the critical code responsible for packaging the probe’s data.

They couldn’t physically replace the hardware, and the remaining functional memory wasn’t large enough to hold a single, contiguous block of the replacement code. So, the engineers performed a masterclass in full-stack problem solving. They sliced the essential code into smaller fragments and tucked those fragments into the scattered pockets of the surviving memory.

However, moving the code broke the abstractions. All the hardcoded memory references and pointers in the original assembly language were now invalid. The team had to trace, recalculate, and rewrite the memory addresses across the entire system to ensure the scattered fragments would still execute as a cohesive whole. They beamed this patch through the void of space, waiting 22.5 hours just for the signal to arrive, and another 22.5 hours to confirm it worked. They essentially refactored a 46-year-old operating system from across the solar system.

Not all of us have the opportunity or need to debug a probe in interstellar space or refactor Google’s search index. However, the courage and the capability to solve the problem by wrestling with the whole stack should be the aspiration of all engineers.

The claim that knowing how to build is no longer important is an illusion. It is an illusion caused by the fact that we are in the booming stage of adopting a new technology. In fact, one would say pretty much the same thing during the dot com boom - knowing what website to build, and being the first to build it is way more important than knowing how to build a website.

Apparently, history has proved it wrong. While building a website appears to be pretty straightforward, running a scalable business behind it is not. Many of them were built out of static web pages, or fragile CGI written to flat files. Most of them don’t have the digital workflow to run an online business. It took many years of engineering effort to build the software stack to make it possible.

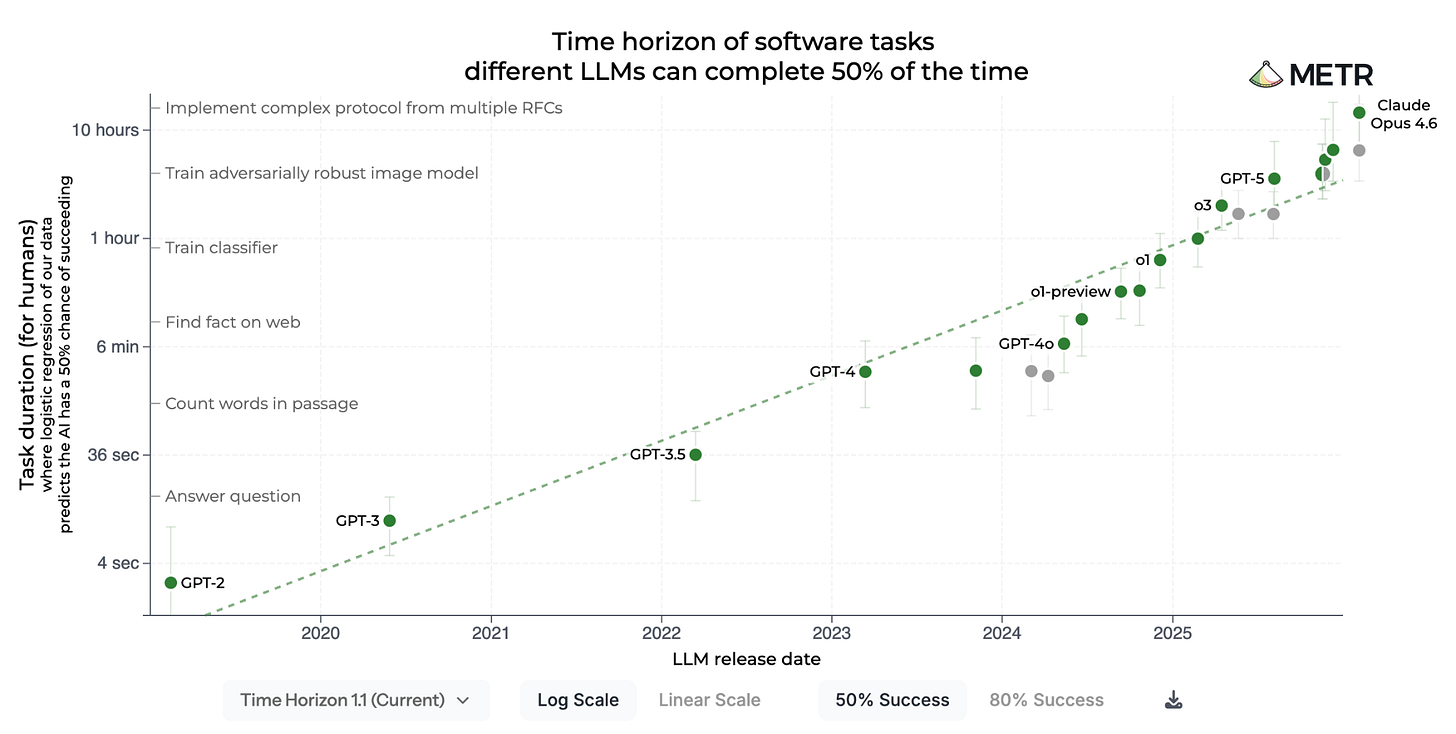

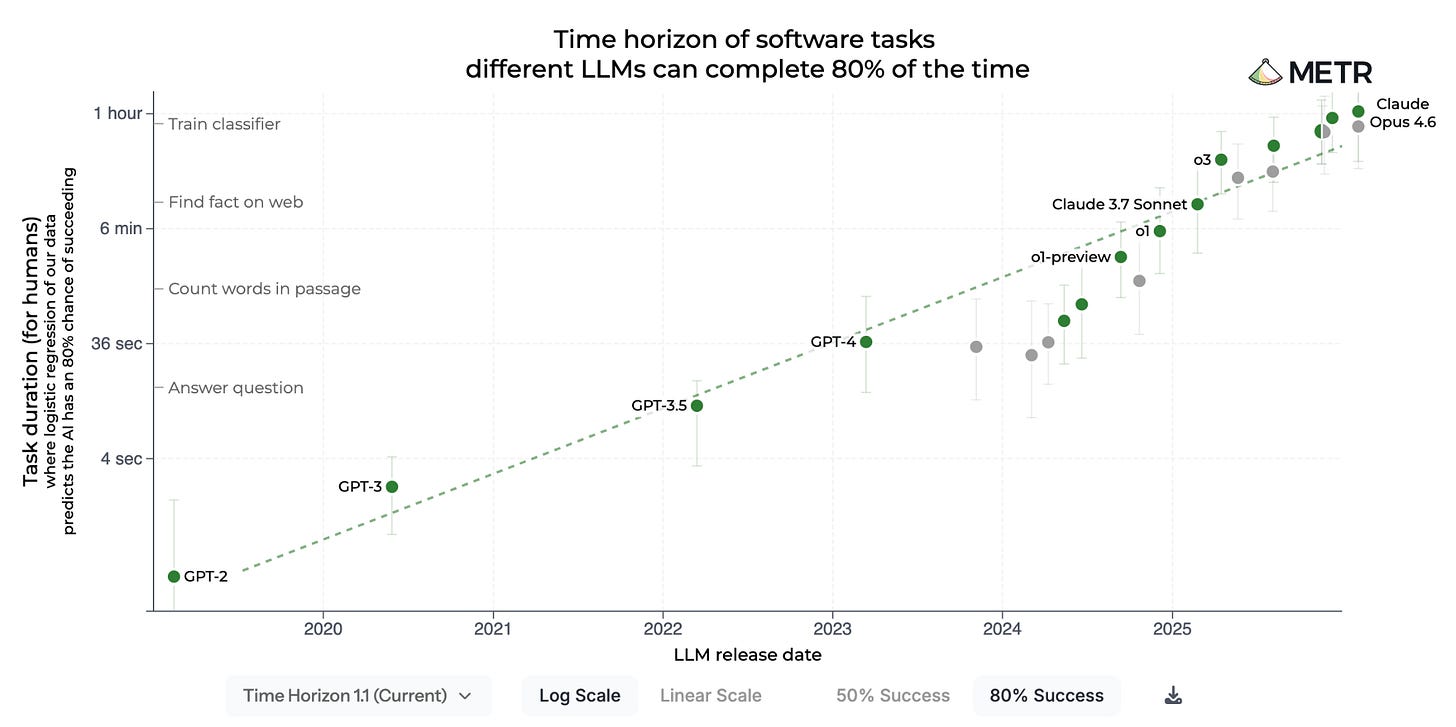

If we examine where AI sits in our layers of abstractions, it is not hard to see that AI is an additional layer of abstraction built on top of software and digital information. It is trained with algorithms written in software, with information collected through software and it generates output using sophisticated inference software. Like other layers of abstraction, it provides a supposedly more convenient interface when it works (e.g. prompting instead of writing code). But when the AI interface breaks down, one has to go back to the layers underneath. AI doesn’t simplify the technical stack; it adds more complexity to it, and it breaks assumptions made in the underlying layers - from hardware to software to societal contracts, all of which have to be redesigned.

Of course, I am not saying AI is just a hype. Even if the dot com bubble burst in 2000, the dreams of moving business online mostly came true 10 - 20 years later. Pushed by capital, we currently live in the brutal “acting out” phase of the adoption of a new technology into society. During the “acting out” phase, all products tend to be naive; all positive or negative sentiments are valid, but they tend to over-simplify. The clash of sentiments are exposing the contradiction between technology and reality, which will be most efficiently solved through engineering at different layers. How much AI can be successful depends on how well we can engineer (instead of marketing) it into society.

A particular area of engineering won’t stay important forever; however, the engineering mindset - the relentless pursuit of building useful layers, and the courage of peering through underlying layers while building, maintaining and improving those layers, will thrive for as long as I can tell.